www.johntyman.com/peru/10.html

|

CULTURES IN CONTEXT PERU The Incas and Prehistoric Cultures IV: INCA CULTURE 4.2: Agriculture and Environment |

099. The empire’s population was fed by intensive agriculture. They grew only local plants, those that were already grown there … notably different types of potatoes and corn… but other cereals and vegetables also, including quinoa on higher, cooler lands. They built terraces on steep slopes served by irrigation channels, and used animal excrement as fertilizer. “They collected it carefully throughout the year, dried it and kept it in powdered form”. (Garciilaso Vega, page167) |

100. On the coast for fertiliser they used the droppings of seagulls and the heads of sardines. They commonly dug a small hole, and put in a sardine head to two, then two or three grains of corn in each one. There were as many varieties of corn as there were of potatoes. |

101. While much of each terrace was made from rocks and gravel available on site, the topsoil was usually carried from lowlands adjacent to the nearest river. Their terraces were broadest at the bottom and narrower towards the top. They were cultivated using a piece of wood rounded at the bottom, and pushed into the soil like a spade. |

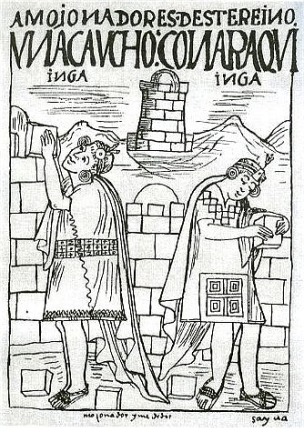

102. All cultivated land was divided into three parts; the first allocated to the Sun, the second to the Inca, and the third to his people. The people’s share was divided into equal parts, each one large enough to support a couple. Each man was given a “tupo” (or plot) to cultivate and his wife half a plot. For each son they were entitled to an additional plot, and half a plot for each daughter. Before any man worked on his own land, he first had to help plough the Sun’s land, next that allocated to the state, then that of widows and orphans, and disabled persons. When he went off to war his wife had the same rights as widows, and her land was worked by her neighbours. (Surveyors measuring fields, pastures, and irrigation channels.) |

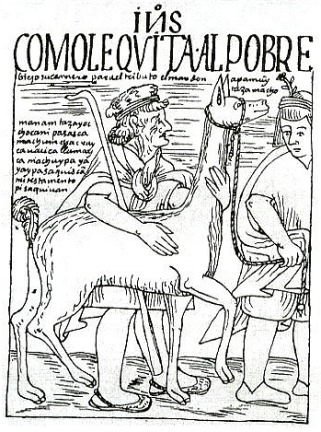

103. The produce of the lands allocated to the Sun and to the state was used to support the army, priests, and administrative officials. The work done by each family on the lands of the Sun and the Inca was part of the tribute paid by all inhabitants of the empire; in addition to which they had to hand over a portion of their own crop, labour on public works projects (sometimes far from their homes), and provide military service. (This old man’s llama was taken because he had not paid his agricultural tax.) |

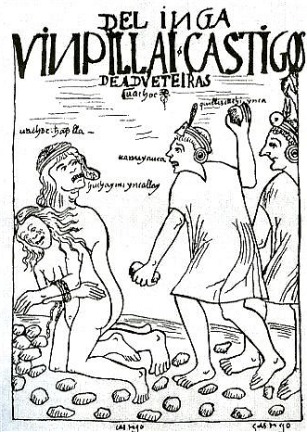

104. Though the Inca king had absolute authority he was not despotic. Justice was based on three principles: do not be idle, do not steal, and do not lie. Murder, theft, adultery and rebelliousness against authority were severely punished: but the disabled, or any person who could not work, received state assistance. This woman and her lover were sentenced to death by stoning. If the man had forced the woman, he would have been sentenced to death and she would have received 200 lashes. |

105. Their vegetable diet was supplemented by fishing and hunting, wherever possible. They also herded llamas and alpacas; and every family kept guinea pigs to eat … just as they do today. (On the floor of a kitchen at Ollantaytambo in 2007.) |

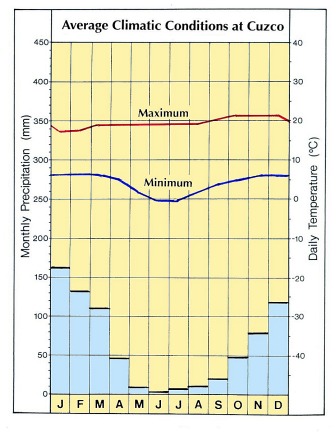

106. Since both Cuzco and Quito lie close to the equator the rhythm to their temperatures year-round is limited, so there was a less obvious seasonal rhythm to farm work here than in middle latitudes. Average daily maxima ranged from 21 to 23 degrees Celsius in both places. The average daily minimum at Quito ranged between 7 and 8 degrees, but Cuzco being further from the equator and at a somewhat higher altitude, experienced daily minima between 7 degrees above zero and one degree below. Both were drier in their (very slightly) cooler “winter” months between May and September. |

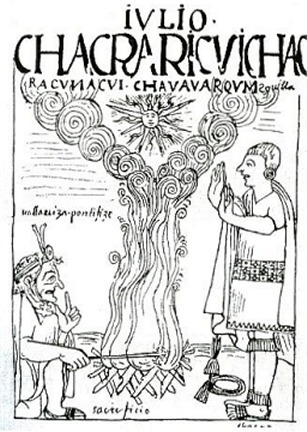

107. Sacrifices were made to ensure favourable weather conditions, rain especially. In July the land was shared out, and one hundred coloured llamas and one thousand white guinea pigs were sacrificed, burned in the main square to ensure that there would be enough rain and sunshine to provide a good crop. |

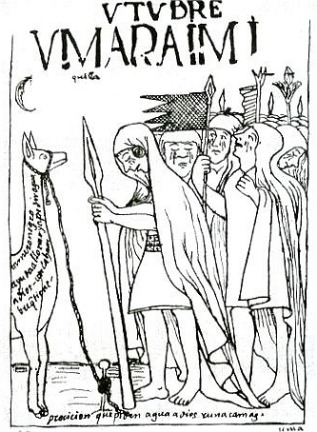

108. In October they sacrificed black llamas, weeping as they prayed, to ensure the Gods sent water from heaven. In December during the great Feast of the Sun “much gold and silver plate is sacrificed to the Sun, together with livestock, …(and) five hundred innocent children, boys and girls, are buried alive, standing upright alongside shrines… After the sacrifice a great feast is held at which they eat and drink to the Sun and dance in the public squares of Cusco and throughout the kingdom; and those who become too drunk, or who turn their heads towards the women, or who blaspheme and use bad language are all put to death.” (Vega page 294) The children were aged between four and ten and had to be perfect sacrifices… without any blemishes, not even a mole. |

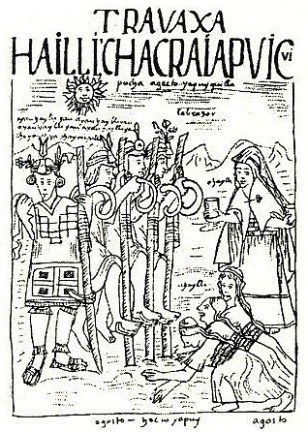

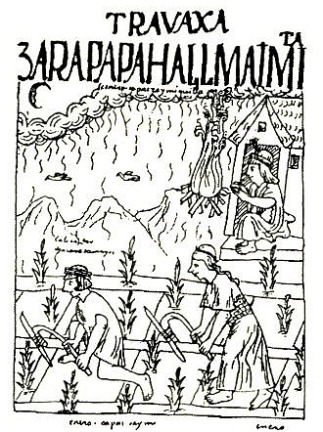

109. The pattern of farm work year-round was, like everything else, recorded in the Chronicle of Guaman Poma, with drawings for each month. In January (shown here) they worked with hoes in potato fields and burnt wood to keep warm at higher altitudes. |

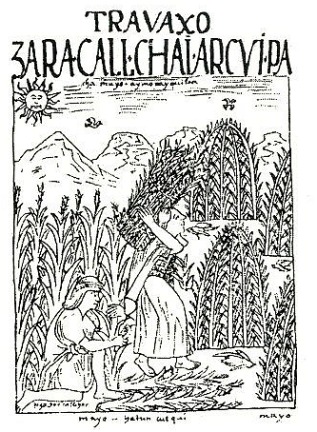

110. Between February and April they were kept busy protecting their crops from foxes, deer, birds and thieves. By April their corn, potatoes and fruit were close to being ripe. The corn was harvested in May (shown here) and carried to communal warehouses |

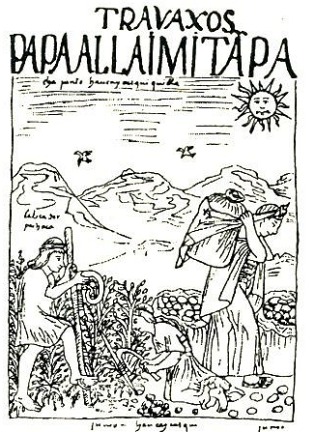

111. In June potatoes were harvested with digging sticks, and carried from the fields for on-farm storage. Grain was harvested in July and stored in state granaries. |

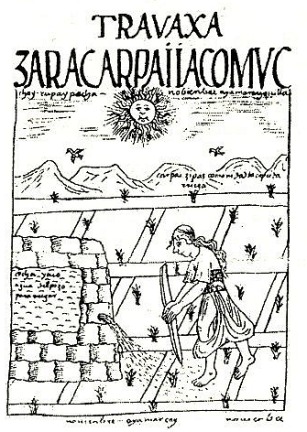

112. The fields were tilled in August and corn was planted in September, guarded in October, and watered constantly in November (as illustrated). Potatoes and quinoa were planted in December. |

![]()

Text and photos by John Tyman

Intended for Educational Use Only.

Contact Dr. John Tyman at johntyman2@gmail.com

for information regarding public or commercial

use.

![]()

www.hillmanweb.com

Photo processing, Web page layout, formatting

and hosting by

William

Hillman ~ Brandon, Manitoba ~ Canada